An Analysis of "MIT Recursive Language Models" Approach

🧠 STOP AI FROM FORGETTING! The End of "Goldfish Memory"

Recursive Language Models

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.24601v1

Alex L. Zhang, MIT CSAIL, altzhang@mit.edu

Tim Kraska, MIT CSAIL, kraska@mit.edu

Omar Khattab, MIT CSAIL, okhattab@mit.edu

Ever feel like your AI has the memory of a goldfish? 🐟 One minute it’s a genius, and the next, it’s completely forgotten what you were talking about.

This isn't just annoying—it’s a scientific phenomenon called "Context Rot." Even the world’s most advanced AI models suffer from it... until now.

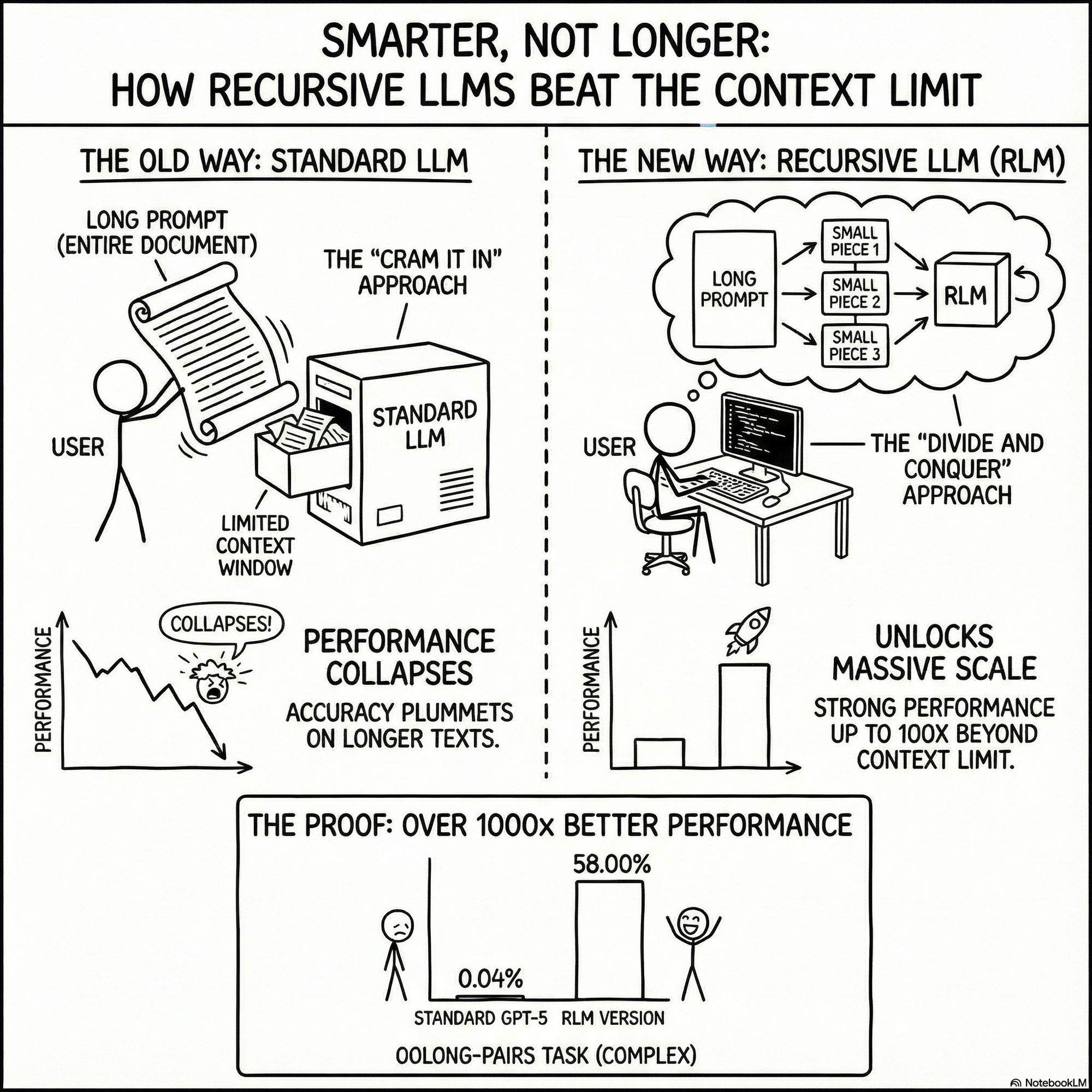

In this post, we break down a breakthrough called Recursive Language Models (RLMs). Instead of just trying to "remember" more, AI is now learning to organize its own brain like a human would.

What’s inside:

📉 The Cliff: Why AI "gets dumber" the more you talk to it.

🚀 The 100x Boost: How new tech is giving AI a nearly infinite memory.

🤖 Agent Power: How AI is now acting as its own project manager to solve impossible tasks.

🔮 The Future: What happens when your assistant can "read" an entire library in seconds?

The "goldfish" days are over. Watch to see how we’re giving AI a memory that never fades.

An Explainer Video:

A Gentle Slide Deck:

Let's Dive In...

1.0 Introduction: The Challenge of Scaling LLM Context

Modern Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities, yet their effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by a critical architectural bottleneck: a limited context window. Overcoming this limitation is of paramount strategic importance, as it would unlock the potential for these models to perform long-horizon reasoning, process massive datasets like entire code repositories, and tackle complex, multi-step tasks that are currently intractable.

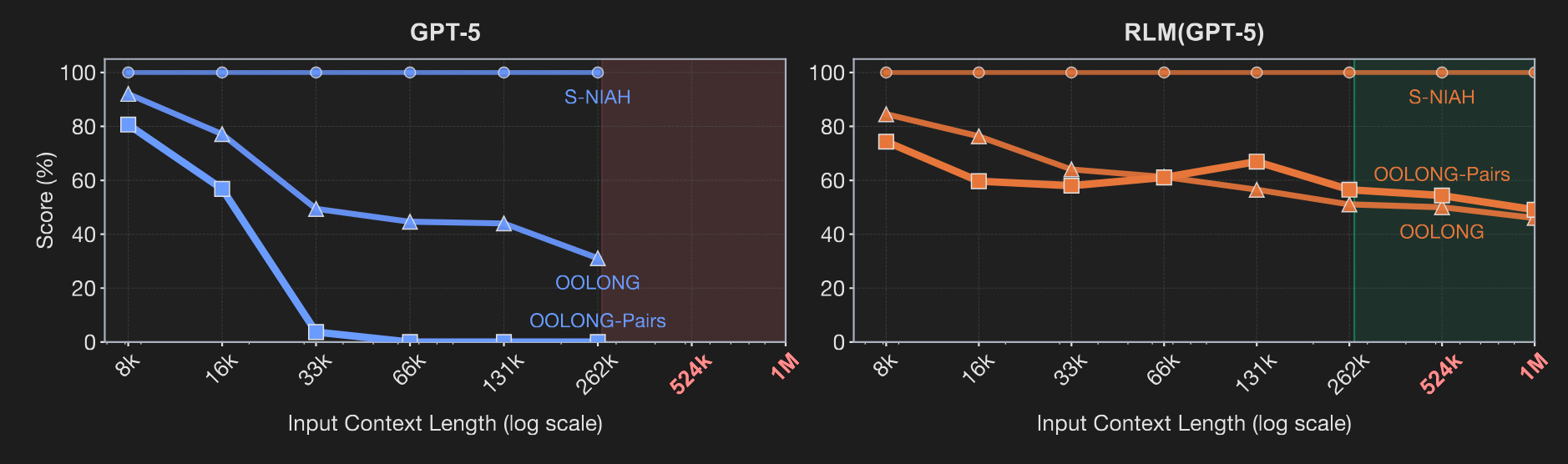

A significant hurdle is the phenomenon of "context rot," a degradation of an LLM's performance as its input grows longer. As the paper hypothesizes and Figure 1 illustrates, this is not a monolithic failure; rather, an LLM's effective context window shrinks as task complexity increases. The performance of a frontier model like GPT-5 degrades significantly as a function of both input length and task complexity, deteriorating progressively from the constant-complexity S-NIAH task to the linear-complexity OOLONG and the quadratic-complexity OOLONG-Pairs.

Common inference-time workarounds, such as "context condensation or compaction," attempt to mitigate this by iteratively summarizing the prompt. However, these methods are fundamentally insufficient for tasks that require dense and repeated access to information spread across a large context. By presuming that early details can be safely compressed, context compaction risks losing the very information that may be crucial for solving the problem, rendering it a lossy and often ineffective strategy.

The paper introduces Recursive Language Models (RLMs) as a novel, general-purpose inference paradigm designed to dramatically scale the effective input length of any LLM. The core thesis is that by reframing how a model interacts with its prompt, RLMs can handle inputs orders of magnitude larger than a model's physical context window while outperforming existing methods. This analysis will delve into the architectural principles, experimental validation, and emergent capabilities of the RLM paradigm.

2.0 The Recursive Language Model (RLM) Paradigm

This section deconstructs the core architecture and inference strategy of RLMs. The novelty of the RLM approach lies not in altering the underlying LLM, but in a fundamental re-conceptualization of the model's interaction with its prompt. The paradigm shift is from treating a long prompt as input to a neural network to treating it as an object in an external environment that the LLM programmatically explores.

The fundamental insight of RLMs is to allow models to "treat their own prompts as an object in an external environment," which they can understand and manipulate by writing code. This is analogous to "out-of-core algorithms" in traditional computing, where a system with limited main memory processes vast datasets by intelligently fetching and managing data from slower, larger storage. In the RLM paradigm, the LLM's context window is the "fast main memory," and the full prompt is the "larger dataset" stored externally.

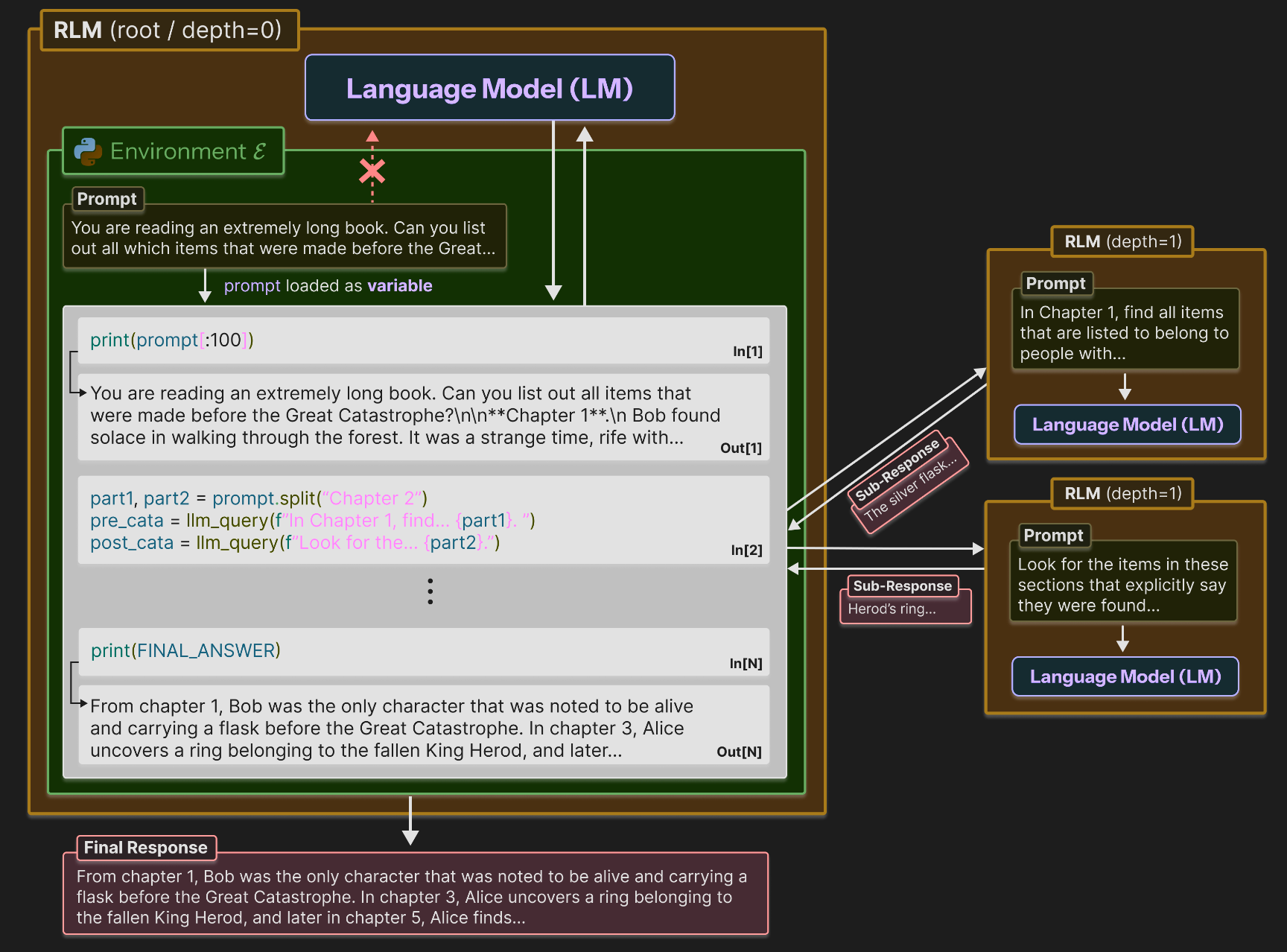

As illustrated in the paper's Figure 2, the RLM inference process unfolds in a structured, programmatic loop:

- Environment Initialization: An RLM establishes a Read-Eval-Print Loop (REPL) environment, specifically using Python. This environment acts as the LLM's workspace.

- Prompt Externalization: The entire long prompt

Pis loaded into the REPL not as direct model input, but as the value of a string variable (e.g.,context). Instead of the full prompt, the model receives only metadata, such as the variable's length and name, forcing it to adopt an exploratory, programmatic mindset from the outset. - Programmatic Interaction: The LLM is then prompted to write and execute Python code within the REPL. This allows it to inspect snippets of the

contextvariable (e.g.,print(context[:100])), search it using tools like regex, and decompose it into manageable chunks. - Recursive Self-Invocation: Crucially, the LLM can programmatically construct new, smaller tasks and call a "sub-LM" on these specific portions of the context. This recursive ability allows the model to delegate complex sub-problems, process chunks in parallel or sequence, and aggregate the results.

This architecture represents a foundational improvement over prior task decomposition methods. While other approaches explore recursive sub-tasking, they are still constrained because the initial, complete prompt must fit within the base LLM's context window. RLMs overcome this by externalizing the prompt, enabling the model to handle inputs of arbitrary length. The following sections explore how this architectural shift was empirically validated.

3.0 Experimental Design and Methodology

The paper's empirical evaluation was designed not just to test performance on long contexts, but also to understand how performance degrades as a function of task complexity, positing that a model's effective context shrinks as reasoning demands increase.

The experiments were grounded in two state-of-the-art LLMs, providing a robust comparison between commercial and open models:

- GPT-5: A closed, commercial frontier model.

- Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B: An open, frontier model.

RLMs were benchmarked against several baseline methods and an important ablation study to isolate the impact of its components:

- Base Model: The standard practice of calling the LLM directly with the prompt.

- Summary Agent: A context compaction approach that iteratively summarizes the prompt.

- CodeAct (+BM25): An agent that uses a code interpreter. Crucially, unlike RLM, CodeAct receives its full prompt directly and does not externalize it, making it fundamentally constrained by the base model's context window.

- RLM (no sub-calls): An ablation study to isolate the impact of the REPL environment without recursive calls.

The evaluation was conducted across five core benchmarks, each chosen to represent a different pattern of complexity scaling.

Benchmark | Task Description | Inherent Complexity Scaling |

S-NIAH | Find a single "needle" in a haystack of text. | Constant |

OOLONG | Semantically transform and aggregate nearly all chunks of the input. | Linear |

OOLONG-Pairs | Aggregate pairs of chunks to construct the final answer. | Quadratic |

LongBench-v2 CodeQA | Multi-choice code repository understanding. | Fixed number of files |

BrowseComp-Plus (1K) | Multi-hop question answering over 1000 documents. | Multiple documents |

This comprehensive experimental design provides a clear basis for analyzing the performance and emergent behaviors of the RLM framework, as detailed in the results that follow.

4.0 Analysis of Results and Performance

The overarching outcome of the experiments is unambiguous: across diverse tasks and models, the RLM framework demonstrated a significant performance advantage over all baselines, particularly as context length and task complexity increased.

4.1 Superior Scaling and Performance on Demanding Tasks

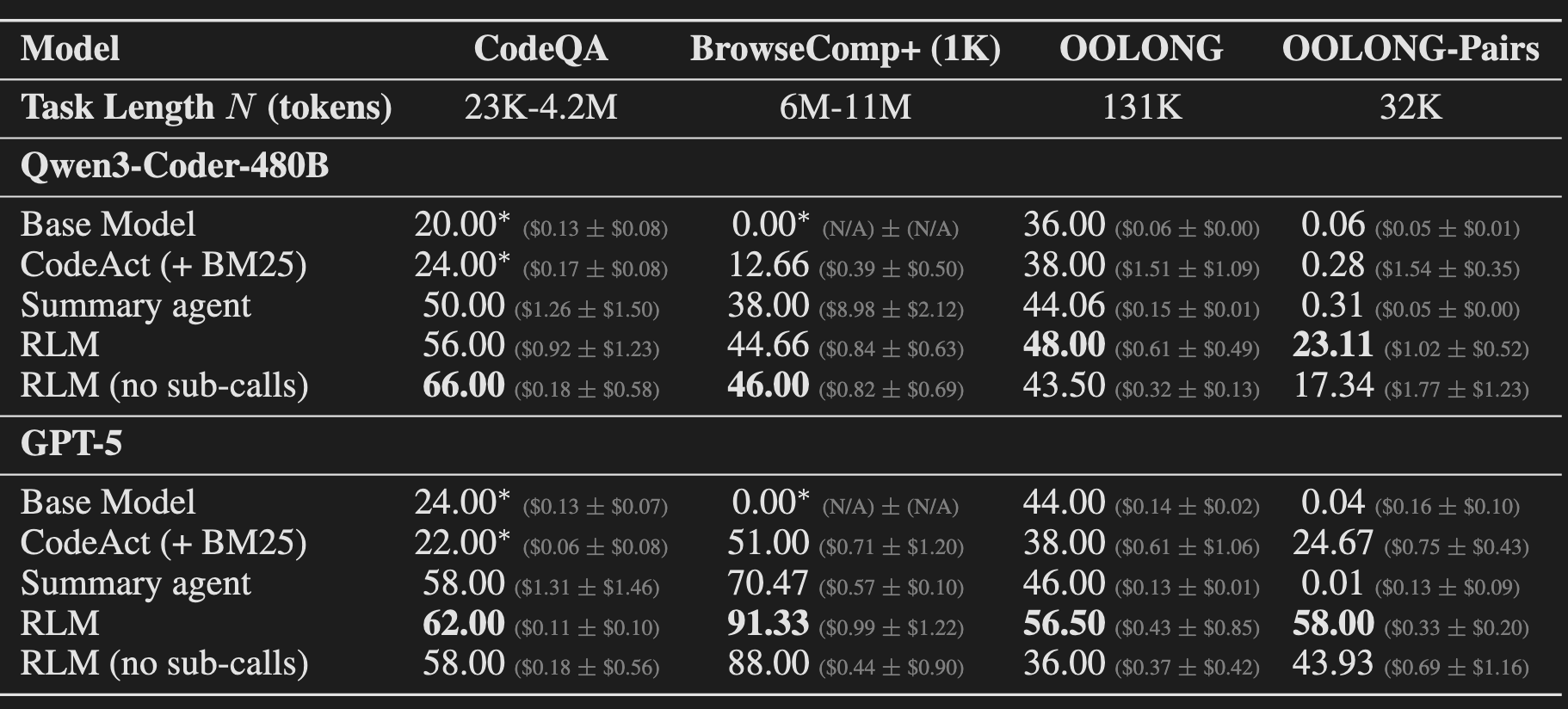

The results presented in Table 1 show that RLMs excel on tasks where base models make little to no progress. On the quadratically complex OOLONG-Pairs task, the base GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder models achieved F1 scores of just 0.04% and 0.06%, respectively. In stark contrast, the RLM implementations achieved scores of 58.00% for RLM(GPT-5) and 23.11% for RLM(Qwen3-Coder). Presenting these results side-by-side substantiates the model-agnostic nature of the RLM paradigm, demonstrating that the framework itself is responsible for the dramatic improvement.

Figure 1 provides a visual anchor for this analysis. While the base GPT-5's performance degrades sharply with longer context and more complex tasks, the RLM maintains strong and stable performance, even on inputs far beyond the base model's physical context window.

4.2 The Distinct Roles of the REPL and Recursion

The RLM (no sub-calls) ablation study, detailed in Observation 2, provides critical insight into a clear separation of concerns within the framework:

- The REPL environment is the key component enabling the model to scale beyond its context window. By offloading the prompt, even the non-recursive RLM could handle arbitrarily long inputs and outperform other baselines.

- Recursive sub-calling is the critical feature for tackling information-dense tasks. On benchmarks like OOLONG and OOLONG-Pairs, the full RLM outperforms the non-recursive ablation by 10%-59%. Recursion allows the model to apply complex reasoning to individual chunks without suffering from the context rot that would occur if processing everything at once.

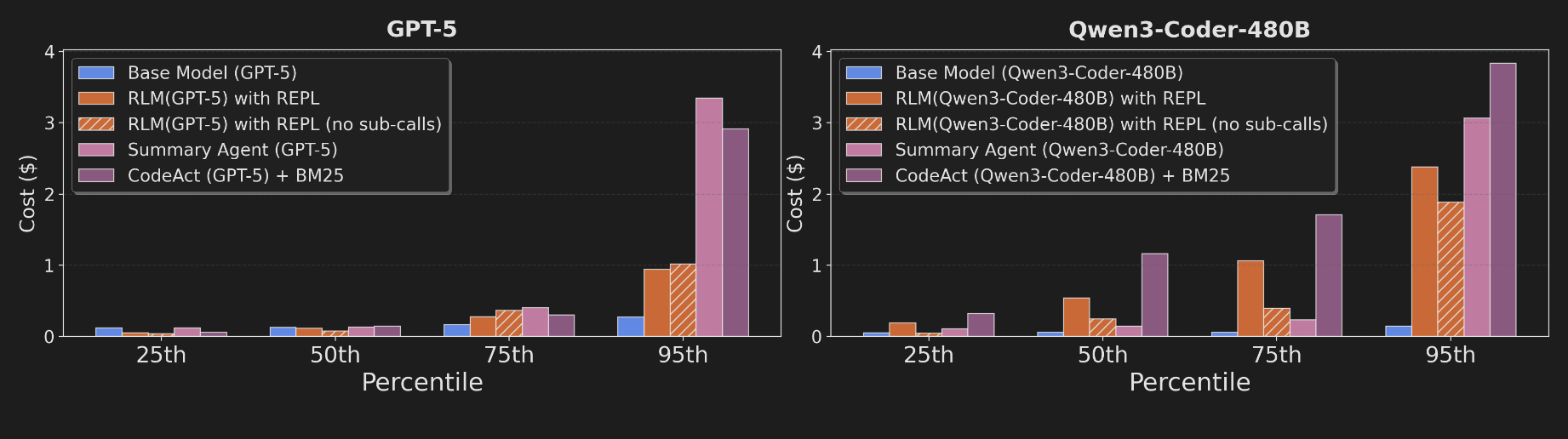

4.3 Inference Cost and Latency Profile

Based on Observation 4 and Figure 3, RLM's median inference cost is comparable to or cheaper than a base model call, but its cost distribution exhibits high variance due to differing trajectory lengths on complex tasks. The ability to selectively view context allows RLMs to be up to 3x cheaper than the summarization agent, which must process the full input. The paper notes, however, that the reported high runtimes are a direct consequence of the implementation, where "all LM calls are blocking / sequential," and could be significantly improved.

4.4 Model-Agnosticism and Behavioral Divergence

The success of the RLM framework with both GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder demonstrates that it is a model-agnostic inference strategy (Observation 5). However, the experiments also revealed significant behavioral differences between the models. RLM(GPT-5) showed superior performance on BrowseComp-Plus, while RLM(Qwen3-Coder) was prone to making excessive, inefficient sub-calls, a behavior requiring a specific prompt modification to mitigate. This suggests that while the framework is general, its optimal implementation may benefit from model-specific tuning.

The next section examines the qualitative reasoning patterns that drive these quantitative results.

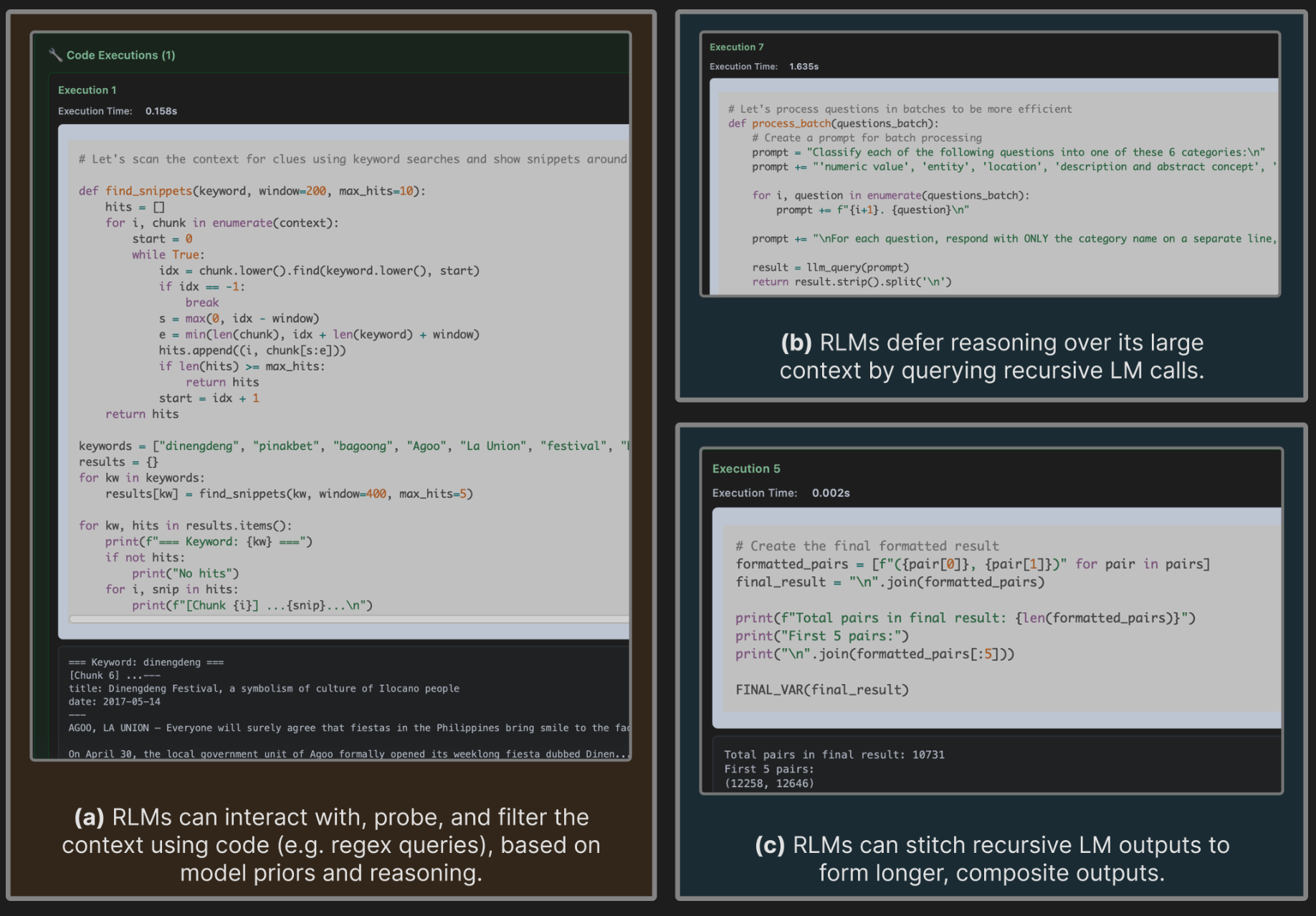

5.0 Emergent Reasoning Patterns and Capabilities

Beyond quantitative metrics, the analysis of RLM trajectories reveals sophisticated, emergent behaviors that demonstrate how RLMs manage and reason over vast contexts without explicit training. These patterns, illustrated in Figure 4, are the underlying mechanisms driving the observed performance gains.

- Dynamic Context Filtering RLMs use their priors to write and execute code (e.g., regex searches for keywords like "festival" or "La Union") to intelligently probe the context. This allows the model to identify and focus on relevant snippets, avoiding the cost and cognitive load of processing millions of irrelevant tokens.

- Programmatic Task Decomposition A common strategy is the programmatic decomposition of a large problem. For information-dense tasks, RLMs were observed chunking the input context (e.g., splitting a text file by newline characters) and applying recursive sub-LM calls to process each chunk individually.

- Unbounded Output Construction By using the REPL to store the outputs of multiple sub-calls in variables and then programmatically stitching them together, RLMs can construct a final answer that far exceeds the base model's token limit. This strategy allows the RLM to effectively circumvent the base model's physical output token limit.

- Iterative Answer Verification RLMs frequently use sub-LM calls to verify or refine information, such as making a targeted recursive call on a snippet to "Re-check the key article...and extract the exact beauty pageant winner details." This helps mitigate context rot but can sometimes lead to redundancy.

These emergent strategies are the underlying mechanisms that explain the dramatic performance gains on information-dense tasks like OOLONG-Pairs and the cost-effective scaling on document analysis tasks like BrowseComp-Plus.

6.0 Discussion: Limitations and Future Directions

The paper contextualizes its findings by acknowledging several limitations, which point toward clear pathways for future research that could further enhance the RLM paradigm.

- The use of a naive implementation where all LM calls are blocking / sequential, which negatively impacts runtime.

- The lack of exploration into deeper recursion, as a max recursion depth of one was used in all experiments.

- The reliance on existing frontier models that were not explicitly trained or fine-tuned to operate within the RLM framework. This limitation directly explains some of the observed results, such as the behavioral divergence and inefficient sub-calling of Qwen3-Coder discussed in Section 4.4.

The most significant area for future work proposed by the authors addresses this third limitation. They hypothesize that RLM trajectories can be viewed as a form of trainable reasoning. This suggests the potential for bootstrapping existing models to generate high-quality reasoning trajectories, which could then be used as training data to explicitly fine-tune new models to be highly efficient "root" or "sub" LMs in an RLM system.

This path forward points toward a co-designed training and inference paradigm, setting the stage for the paper's conclusion.

7.0 Conclusion

The "Recursive Language Models" paper introduces a general and effective inference-time framework for overcoming the critical context limitations of modern LLMs. The central mechanism—externalizing the prompt into a REPL environment to enable programmatic interaction and recursion—is a fundamental redefinition of the model-prompt relationship. The empirical results are decisive, demonstrating that RLMs can process inputs orders of magnitude larger than a base model's context window while achieving superior performance on tasks of varying complexity. RLMs establish a viable and powerful paradigm for scaling the effective reasoning capacity of language model systems, enabling a new class of long-horizon AI applications.

fin...