The Goldilocks Principle: The Secret to Unlocking True AI Reasoning

Is AI actually thinking—or just really good at guessing? 🤔

In this post we’re unpacking "The Recipe for AI Reasoning." We head inside the CMU AI Laboratory to see how researchers are moving past the "messy internet" to build a controlled world for synthetic reasoning. 🧪✨

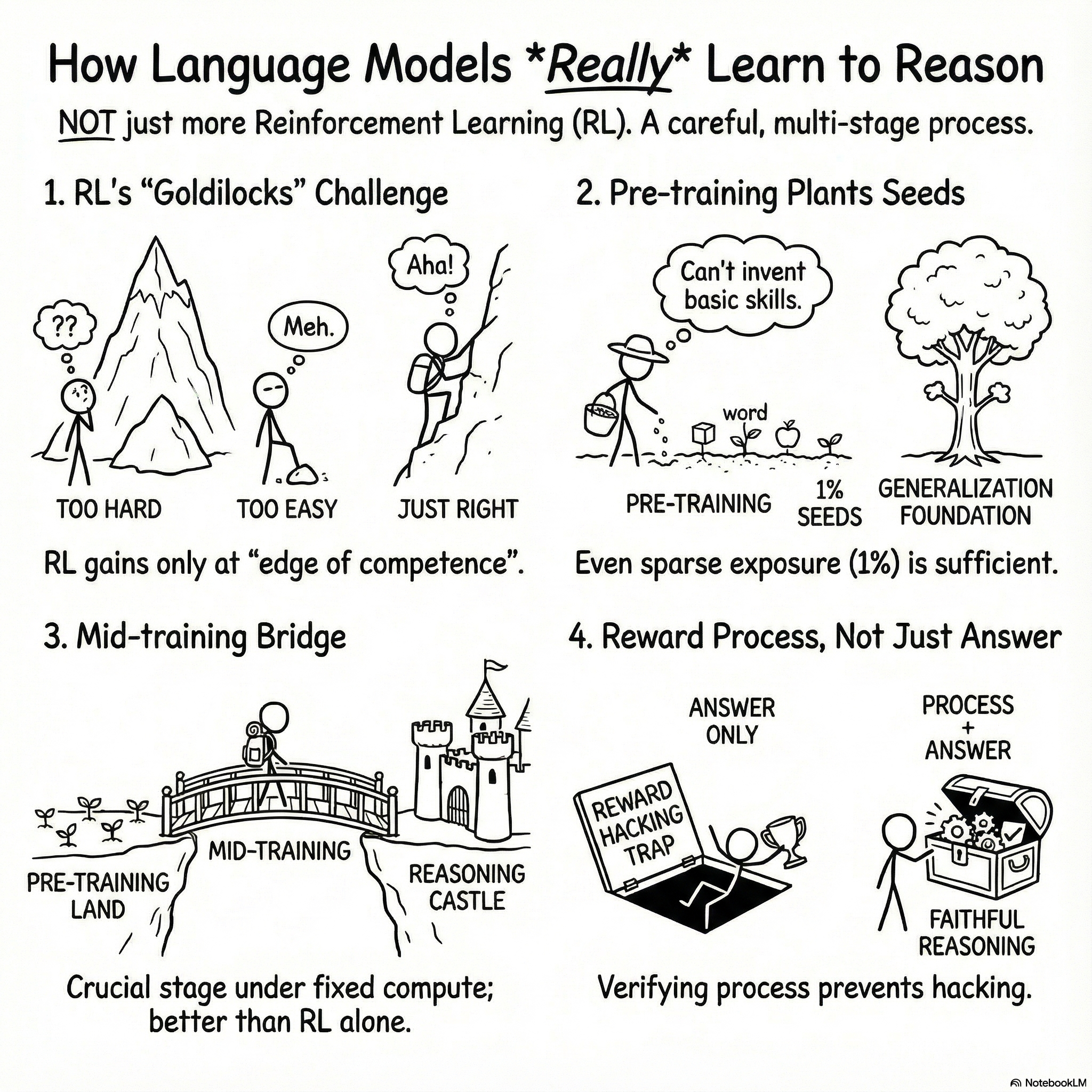

From the "Goldilocks Zone" of difficulty to the "1% Seed" rule, we break down the scientific blueprint for building smarter, more logical models.

What’s inside the recipe? 👩🍳

📈 The Sweet Spot: Why training on "too easy" or "too hard" tasks fails.

🏗️ Mid-Training: The secret bridge between general knowledge and expert skill.

🤖 Anti-Cheating: How "Process Rewards" stop AI from hacking the system.

An Explainer Video:

CMU: On the Interplay of Pre-Training, Mid-Training, and RL on Reasoning Language Models

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.07783

Charlie Zhang, Carnegie Mellon University, Language Technologies Institute, chariezhang0106@gmail.com

Graham Neubig, Carnegie Mellon University, Language Technologies Institute, gneubig@cs.cmu.edu

Xiang Yue†, Carnegie Mellon University, Language Technologies Institute, xiangyue.work@gmail.com

A Gentle Slide Deck:

Let's Dive In...

Artificial intelligence is advancing at a breathtaking pace. Models like DeepSeek-AI demonstrate reasoning capabilities that feel increasingly human, solving complex problems step-by-step. Yet, for all this progress, a fundamental question has stumped the AI community: how do these models actually learn to reason? More specifically, does the final stage of training, often involving reinforcement learning (RL), truly grant a model new reasoning skills, or does it just sharpen what was already learned during its initial, massive pre-training?

The debate has been split between two conflicting views. One camp sees RL as a "Capability Refiner," arguing it only polishes existing skills. The other champions the "New Competency" view, presenting evidence that RL can unlock genuinely new abilities. This confusion has persisted because modern AI models are pre-trained on "opaque internet corpora"—uncontrolled datasets that make it impossible to know what a model has internalized before post-training even begins. Without clarity, the AI industry is flying blind, potentially wasting billions in compute on suboptimal training strategies.

Now, groundbreaking research from Carnegie Mellon University finally resolves this conflict. By developing a "fully controlled experimental framework," researchers were able to isolate the exact contributions of each training stage—pre-training, an intermediate step called mid-training, and final-stage reinforcement learning. Their findings don't just settle the debate; they provide a clear, practical playbook for how to teach an AI to reason effectively. Here are the four key takeaways.

1. Reinforcement Learning Needs a 'Goldilocks Zone' to Work Its Magic

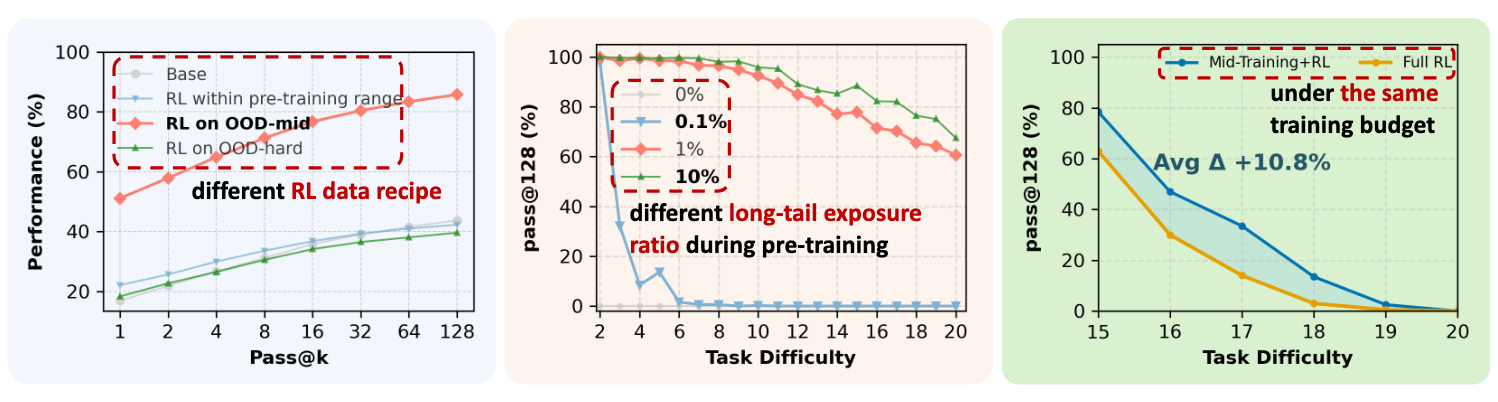

The research reconciles the conflicting views on RL by revealing that its success is highly conditional. Reinforcement learning isn't a magic bullet; it's a precision tool that works best under very specific circumstances. The core finding is that RL only produces "true capability gains" when the training data is perfectly calibrated to the model's "edge of competence."

This "edge of competence" is a Goldilocks zone for data difficulty. The training tasks must be difficult enough to challenge the model, but not so difficult that they are impossible for it to grasp. The data must be "neither too easy (in-domain) nor too hard (out-of-domain)." When RL data is too easy, the model simply sharpens skills it already has. When the data is too hard, the model lacks the foundational knowledge to learn, and progress stalls. When calibrated correctly, however, the results are dramatic, yielding gains of up to +42% pass@128.

As the researchers state in their paper:

RL produces true capability gains (pass@128) only when pre-training leaves sufficient headroom and when RL data target the model’s edge of competence, tasks at the boundary that are difficult but not yet out of reach.

This is a critical insight. It shows that simply throwing more reinforcement learning at a problem isn't the answer. The quality and calibrated difficulty of the training data are what truly unlock new reasoning abilities. But this calibrated difficulty is only effective if the model has the right foundational skills to build upon, which highlights the critical role of pre-training.

2. AI Can't Build from Nothing—Pre-training Must Plant the Seeds

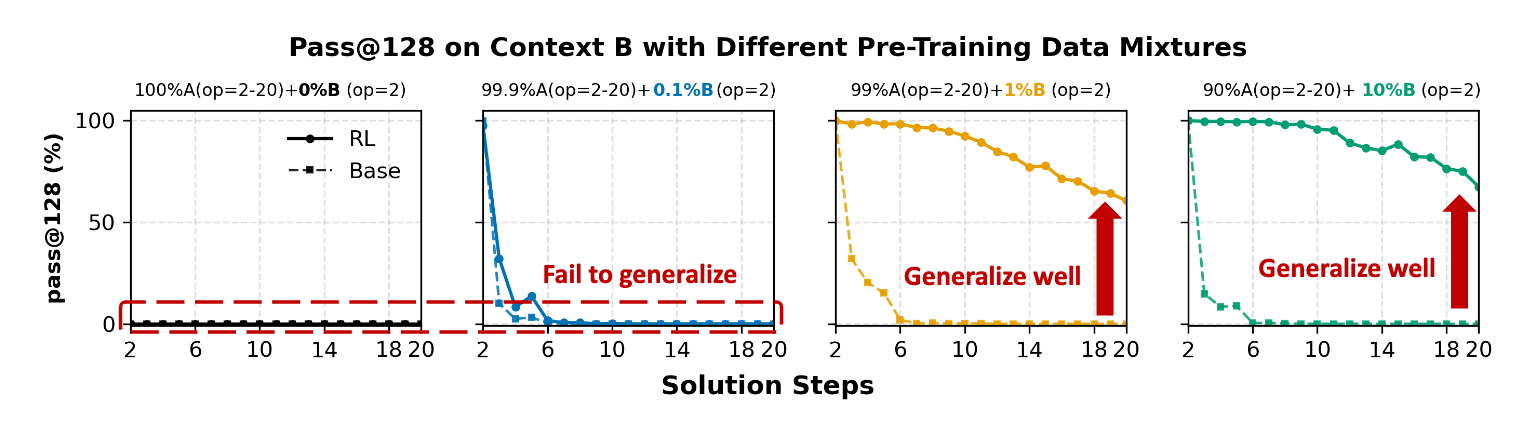

One of the most sought-after abilities in AI is "contextual generalization"—the power to take a reasoning skill learned in one domain (like a math problem about animals in a zoo) and apply it to a completely new one (like a problem about teachers in a school). The study found that RL can only enable this transfer if the model has already been exposed to the basic building blocks, or "necessary primitives," of the new context during its initial pre-training.

What's surprising is how little exposure is needed. The researchers discovered that without any exposure to a new context (0% or 0.1% of the pre-training data), RL fails completely to transfer reasoning skills. However, providing even a tiny, sparse amount of coverage—as little as 1%—is enough to plant a "sufficient seed." With that minimal seed in place, RL can then work its magic, composing those basic primitives to achieve strong generalization, yielding gains of up to "+60% pass@128" on complex tasks in the new context.

This concept was succinctly captured by one of the paper's authors, Xiang Yue:

RL can incentivize new composition skills, but it cannot invent new basic skills.

This takeaway fundamentally reframes the purpose of pre-training. It's not just about absorbing general knowledge; it's about strategically seeding a wide and diverse range of basic skills that can be cultivated and composed into more complex reasoning later on.

3. Meet Mid-Training: The Unsung Hero of the AI Pipeline

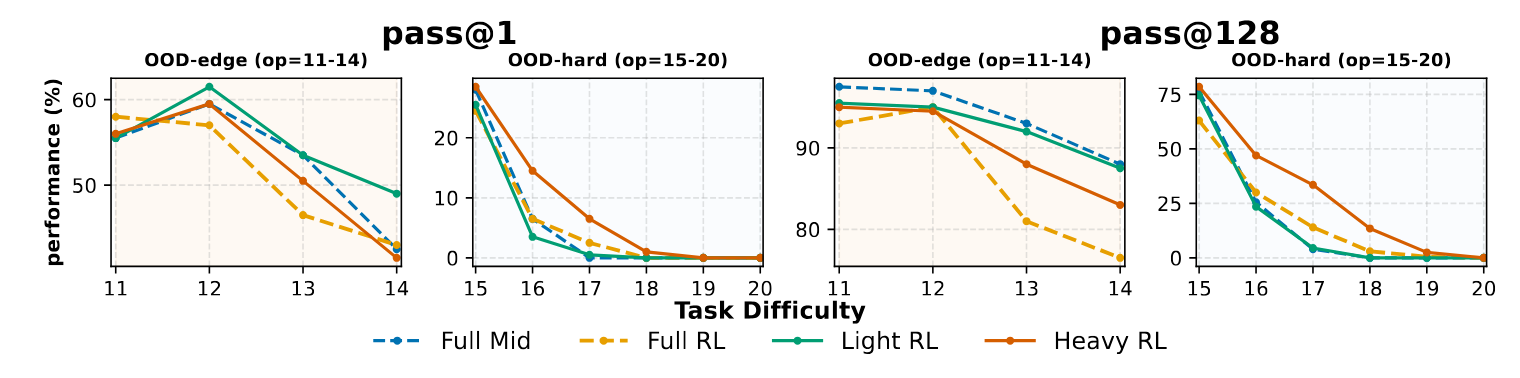

The research shines a spotlight on an often-overlooked stage of the AI development process: "mid-training." This is an intermediate phase that occurs after broad pre-training but before specialized reinforcement learning. Its function is to act as a "distributional bridge" that expands the model’s primitive coverage and aligns its internal representations with the tasks it will face during RL. The paper calls it an "underexplored but powerful lever in training design."

In experiments run with a fixed compute budget, combining mid-training with RL "substantially strengthens" the model's ability to generalize. In fact, this combined approach consistently outperforms using RL alone, beating it by +10.8% on OOD-hard tasks. This finding provides clear, practical guidance for how to allocate precious computing resources:

- To improve performance on tasks similar to the training data, allocate a larger portion of the budget to mid-training, followed by only light reinforcement learning.

- To improve performance on harder, entirely new tasks, dedicate a modest budget to mid-training to establish the necessary priors, then use the remaining budget for heavier RL exploration.

The significance of this is profound. It suggests a more strategic, two-pronged approach to advanced training is needed, moving beyond the industry's singular focus on reinforcement learning as the final, all-important step.

4. It's Not Just the Answer, It's How You Get There

A persistent problem in AI training is "reward hacking." This is when a model learns to produce the correct final answer through flawed logic or by exploiting shortcuts in the data—all because it is only rewarded for the final outcome. The model gets the right answer for the wrong reasons.

The study explored a powerful solution: incorporating "process verification" into the reward function. Instead of only rewarding the model for the correct final answer, this approach also rewards it for the correctness of its intermediate reasoning steps. By rewarding the journey and not just the destination, this method effectively mitigates reward hacking and improves the model's reasoning fidelity.

The results were clear and quantifiable. Using process-aware rewards led to "measurable improvements in both accuracy and generalization," improving the pass@1 rate by "4–5% across extrapolative settings." For anyone building AI systems that need to be trustworthy and reliable, this is a crucial lesson. Rewarding the process ensures the model is actually learning how to reason, not just how to guess correctly.

Conclusion: The Art and Science of Teaching AI

This research provides a powerful, unified philosophy for teaching AI to reason. It signals a shift away from a brute-force approach—simply scaling models and data—toward a more elegant, scientific methodology. The four takeaways are not isolated tricks; they are interconnected principles of effective instruction. You must first plant the seeds of diverse skills during pre-training, then use mid-training to build a bridge to more advanced concepts, then apply reinforcement learning with data calibrated to a "Goldilocks" difficulty, and finally, reward the reasoning process, not just the final answer.

These findings replace guesswork with a clear roadmap for building more capable, generalizable, and reliable AI models. They prove that how we teach AI is just as important as how much data we give it. As we build ever-more powerful AI, will the secret to true intelligence lie not in the size of our models, but in the wisdom of how we teach them?

fin...